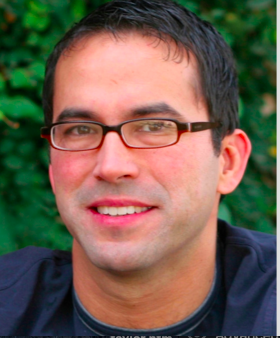

The editorial board of Analytic Philosophy has selected “A Theory of Sense-Data,” by Andrew Y. Lee, as the winning entry for the 2024 Sanders Prize in Philosophy of Mind. Andrew Lee is currently Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto. Previously, he was postdoctoral fellow at Rice University (2019-20), at the University of Oslo (2020-22), and at the Australian National University (2022-23). He received his Ph.D. in philosophy from the New York University in 2019 and did his undergraduate work at Brown University. His main research interest is in philosophy of mind; and he works also on issues in epistemology, ethics, metaphysics, philosophy of language, and philosophy of science. The selection committee awarded the prize after a blind review of 21 submitted papers.

Andrew Y. Lee is an Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Toronto. His main research project is on the structure of consciousness. His work examines how structural concepts—DEGREES, DIMENSIONS, CONTINUITY, DISCRETENESS, PARTS, WHOLES, ISOMORPHISMS, and COMPOSITIONALITY—can be applied to conscious experiences. But he’s interested in many philosophical topics, including also perception, introspection, attention, analog representation, locations, quantities, welfare, and value.

Abstract:

I develop and defend a sense-datum theory of perception. My theory follows the spirit of classic sense-datum theories: I argue that what it is to have a perceptual experience is to be acquainted with some sense-data, where sense-data are private particulars that have all the properties they appear to have, that are common to both perception and hallucination, that constitute the phenomenal characters of perceptual experiences, and that may be aptly described as pictures inside one’s head. But my theory also diverges from conventional sense-datum theories in some key respects: on my view, (1) sense-data are neural states presented first-personally, (2) the sensational qualities of sense-data differ in kind from the sensible qualities of external objects, and (3) sense-data are the vehicles in virtue of which we perceive, rather than the objects that we perceive. I argue that this package of claims is appropriately labeled ‘sense-datum theory’, and that the resultant view ought to be a live contender in contemporary philosophy of perception.